Everything is linked, even if you’ve forgotten you linked them

Walk into most cybersecurity seminars, product demonstrations or corporate training sessions and you’d be forgiven for thinking that antimalware platforms are the savior of humanity.

LAN-based Security-as-a-Service is undoubtedly here to stay, but the most clear and present danger to corporate IT infrastructures across the globe can’t be solely combated with virus definitions, or all-singing-all-dancing gateway devices. If irreparable financial and reputational damage is the potential problem, the most pressing solution lies in the most unassuming of places – your public DNS records.

What are sub-domain takeovers?

On a basic level, subdomain takeovers occur when hackers gain unfettered access to one or more subdomains within an organization’s DNS records.

In technical terms, it’s usually a CNAME record (although NS, A records and even mail records are vulnerable) that’s no longer pointing to a valid source, and it can happen to anyone. A few years ago, researchers discovered no less than 670 Microsoft subdomains that were wide open to an attack.

Subdomain takeovers feature a number of different attack vectors that are usually a heady mix of opportunism and good old-fashioned bad housekeeping. Let’s take a look at two common intrusion methods.

Expired subdomains

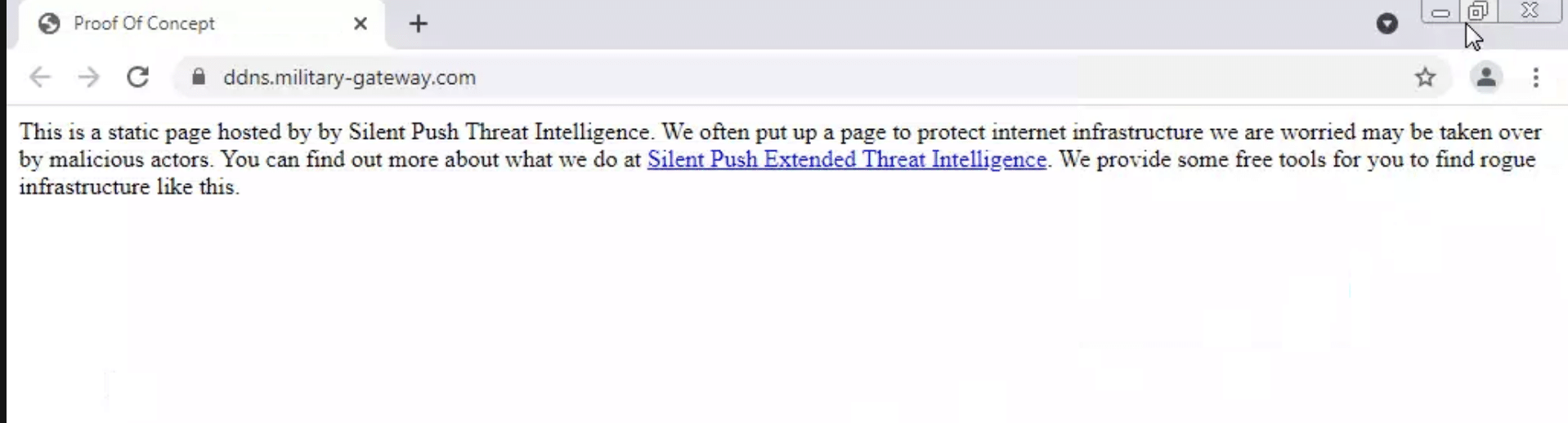

When organizations allow a subdomain to expire, but forget to remove the DNS record associated with it in their main domain, what was once a legitimate subdomain prefix is now up for grabs to anyone who wants it, along with a ready-made backdoor onto an organization’s public DNS platform.

Non-existent services

Even if you have your DNS records in relatively good order, you’re still not safe. If one of your subdomains is directed at an external service that has either been moved elsewhere, or removed entirely, a threat actor is able to establish a presence on said service with the invalid subdomain – also called a “dangling DNS attack” – and with a little CNAME magic, it’s theirs.

The trouble with cookies…

The consequences of a subdomain takeover are many and varied – from XSS attacks to email spoofing – but the one that organizations need to be most wary of are compromised session cookies, and again, it comes down to a lackadaisical approach to DNS security.

If your organization shares browser cookies across some or all of your subdomains, and one of those subdomains is hijacked, you run the risk of not only allowing a threat actor to utilize hashed credentials stored in the cookie and authenticating themselves as a user, but exposing your company-wide SSO service, and all that it provides access to.

A modern problem

As with most cybersecurity threats, subdomain takeovers’ risk level is directly proportional to how difficult it is to detect and combat, and grows exponentially with the size of the organization, and the amount of subdomains they operate with.

The explosion of SaaS-based commerce and cloud service platforms over the last decade has given rise to innumerable third-party platforms that require some form of DNS validation. This phenomenon – coupled with aggressive marketing tactics that often require companies to register numerous subdomains to validate landing pages and individual products and services – means that low-hanging DNS records, and the session cookies and hashed credentials they provide access to, are becoming more and more of a commodity for threat actors around the world.

It’s not just an issue with how modern domains are structured. Well-established security countermeasures are ill-equipped to deal with the kind of DNS oversights that lead to domain takeovers. PKI certificates – whilst always advisable on any network – aren’t much use with compromised cookies, and no amount of endpoint protection will prevent a threat actor from accessing your public DNS records, should they have the means to do so.

Common countermeasures

Fortunately though, it’s not all doom and gloom. There are a number of ways that organizations can operate with a secure set of DNS records and simultaneously improve WAN security across the board, not limited to close management of topic-specific factors such as wildcard certs that provide a threat actor with blanket access to any domain associated with them.

First and foremost, organizations need to treat their DNS records with the TLC that they deserve, and recognise that corporate cybersecurity doesn’t begin and end with

endpoint security. CTOs and CISOs need to keep a firm grip on every last subdomain, and maintain an understanding of what services are being used and whether they’re still in use – e.g. when formulating workflows for decommissioning services, be sure to add a line entry that specifies a CNAME removal

As well as internal governance, it pays to be skeptical. If your organization is thinking about using an external service that incorporates DNS functionality and subdomain registrations, don’t be afraid to ask their onboarding team about how they specifically protect against subdomain takeovers. If they’re good, they’ll be able to tell you about common countermeasures such as linked TXT entries, or banning re-registrations. If they seem unsure about what you’re asking, alarm bells should be ringing.

Looking ahead

Last year witnessed a 20% increase in apex and subdomain takeovers. Threat actors are constantly on the lookout for the next big thing, and they may just have found it. Data from our own threat protection platform has identified almost 3 million global DNS entries that are ripe for the picking as dangling records – 2.7 million CNAMES and over 300,000 NS records. There are also 3.9 million MX records dangling but less likely to be taken over.

The problem isn’t limited to small-time SaaS/PaaS/IaaS platforms with a laid-back approach to DNS security. This is an issue that affects the world’s largest cloud service providers – the very same providers who are supposed to operate with the most sophisticated threat models the industry has to offer. Our own data shows 70 expired services on Microsoft Azure’s content delivery network (azureedge.net) with an attached domain, that run the risk of being hijacked, and nearly 80 of the same across the global GitHub platform.

In the same way that law enforcement authorities need to focus more on the individuals that provide criminals with access to ransomware platforms, rather than the criminals themselves, the security community needs to evangelize less about malware as an existential cyber threat, and shout from the rooftops about subdomain takeovers and cookie hijacking as the next major development in enterprise-level threat protection.